A Winter at Valley Forge

Valley Forge National Park

Valley Forge, Pa.

August 2nd, 1999

As  we travel

through this land, looking for its history, we could not pass up

an opportunity to stop at one of the high points in the beginning

of our country. The year was 1777, The United States had existed

for only a year. The Continental Congress had established itself

in Philadelphia. General Washington found himself in command of a

undisciplined and untrained army made up of brigades from the

different States, each with its own commander. It was not an

army without experience. It was fresh from the disastrous attempt

to stop the British from taking Philadelphia at the battle of

Brandywine and later at Georgetown. Philadelphia had fallen and

the Congress had fled to York. The summer's campaigns had left

the Continental Army short on food and supplies. Washington made

the decision to dig in for the winter just 18 miles out of

Philadelphia on the Schuylkill River in an area named for an iron

forge on Valley Creek nearby. Thus began the famous winter at

Valley Forge. Washington rode into Valley Forge

we travel

through this land, looking for its history, we could not pass up

an opportunity to stop at one of the high points in the beginning

of our country. The year was 1777, The United States had existed

for only a year. The Continental Congress had established itself

in Philadelphia. General Washington found himself in command of a

undisciplined and untrained army made up of brigades from the

different States, each with its own commander. It was not an

army without experience. It was fresh from the disastrous attempt

to stop the British from taking Philadelphia at the battle of

Brandywine and later at Georgetown. Philadelphia had fallen and

the Congress had fled to York. The summer's campaigns had left

the Continental Army short on food and supplies. Washington made

the decision to dig in for the winter just 18 miles out of

Philadelphia on the Schuylkill River in an area named for an iron

forge on Valley Creek nearby. Thus began the famous winter at

Valley Forge. Washington rode into Valley Forge on December 19, 1777, with twelve thousand troops, a few dozen

cannons and not much more. Within days, the waters of the

Schuylkill river were frozen and six inches of snow lay on the

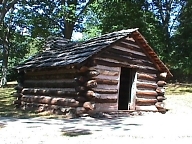

ground. The army, organized according to their brigades, set about

building what would finally be over a thousand huts. While

wandering the grounds in the warm sunlight of August, it was hard

to picture the cold and wet of the winter. To imagine thousands

of men huddled in these little huts for months on end. It fell to

the individual states to support their own brigades, so those

furthest away such as the Carolinas suffered most while the

Pennsylvania brigade fared much better. Food, clothing, shoes and

blankets were always in short supply. Cold and hunger prevailed

throughout the winter. Illness quickly spread through the cramped

quarters filled with weakened men. Soon the

on December 19, 1777, with twelve thousand troops, a few dozen

cannons and not much more. Within days, the waters of the

Schuylkill river were frozen and six inches of snow lay on the

ground. The army, organized according to their brigades, set about

building what would finally be over a thousand huts. While

wandering the grounds in the warm sunlight of August, it was hard

to picture the cold and wet of the winter. To imagine thousands

of men huddled in these little huts for months on end. It fell to

the individual states to support their own brigades, so those

furthest away such as the Carolinas suffered most while the

Pennsylvania brigade fared much better. Food, clothing, shoes and

blankets were always in short supply. Cold and hunger prevailed

throughout the winter. Illness quickly spread through the cramped

quarters filled with weakened men. Soon the makeshift hospitals were filled to capacity. There was no

medicine and few to care for the sick. Many considered being

taken to the hospital a one way trip. By the end of the winter

over 2000 of his men has perished from malnutrition and disease

and another 4000 had deserted. The few scattered farm houses in

the area were converted to military use, with Washington setting

up his headquarters at the Issac Potts House. The modest two

story stone building stands today as a museum to the Military

commander it served. We strolled through the park surrounding the

house trying to picture the hustle and bustle of a headquarters

piled with snow all around. The rooms are laid out much as they

would have been during that winter. From here, Washington planned

to hold his band of untrained farmers together until

makeshift hospitals were filled to capacity. There was no

medicine and few to care for the sick. Many considered being

taken to the hospital a one way trip. By the end of the winter

over 2000 of his men has perished from malnutrition and disease

and another 4000 had deserted. The few scattered farm houses in

the area were converted to military use, with Washington setting

up his headquarters at the Issac Potts House. The modest two

story stone building stands today as a museum to the Military

commander it served. We strolled through the park surrounding the

house trying to picture the hustle and bustle of a headquarters

piled with snow all around. The rooms are laid out much as they

would have been during that winter. From here, Washington planned

to hold his band of untrained farmers together until  spring

when he knew he must face and defeat the professionally trained

British army or watch the colonies be forced back under British

rule. The situation was desperate, the prospects bleak, when,

into the midst of the misery rode one of America's unsung heroes.

On a cold February morning, the tall Prussian officer stood

before Washington with a letter of introduction signed by

Benjamin Franklin. He had been a one time member of the General

Staff of Frederick the Great, king of Prussia, but had found

himself unemployed in France when Ben Franklin talked him into

joining the Continental cause. Fredrich Wilhelm von Steuben

brought with him a wealth of knowledge which Washington saw as a

possible answer to one of his biggest challenges. He immediately

appointed von Steuben acting Inspector General with he task of

developing an effective training program. Numerous obstacles

threatened success. No standard American training manuals existed

and von Steuben himself spoke little English. Undaunted, he

drafted his own manual in French, His aids often worked late into

the night translating his work into English which in turn was

passed out to the individual regiments.

spring

when he knew he must face and defeat the professionally trained

British army or watch the colonies be forced back under British

rule. The situation was desperate, the prospects bleak, when,

into the midst of the misery rode one of America's unsung heroes.

On a cold February morning, the tall Prussian officer stood

before Washington with a letter of introduction signed by

Benjamin Franklin. He had been a one time member of the General

Staff of Frederick the Great, king of Prussia, but had found

himself unemployed in France when Ben Franklin talked him into

joining the Continental cause. Fredrich Wilhelm von Steuben

brought with him a wealth of knowledge which Washington saw as a

possible answer to one of his biggest challenges. He immediately

appointed von Steuben acting Inspector General with he task of

developing an effective training program. Numerous obstacles

threatened success. No standard American training manuals existed

and von Steuben himself spoke little English. Undaunted, he

drafted his own manual in French, His aids often worked late into

the night translating his work into English which in turn was

passed out to the individual regiments.  As

we passed to the rear of the house we met Marc Brier, dressed in

the traditional uniform of the Continental soldier. He explained

that "Von Steuben even shocked some of his fellow officers

when he hand picked 100 men from the field to personally train as

a unit." This unit quickly became the model by which other

training was measured. Day and night, von Steuben's commanding

voice could be heard in camp, directing, correcting and

re-directing. As regiments and then brigades began to pull

together in a single fighting force, pride and enthusiasm

re-emerged among the ranks and spirit of the army was rekindled.

As spring arrived new supplies and more men poured into the

valley and there was now a new alliance with France to bolster

their flagging spirits. On June 19, 1778, Washington marched out

of Valley Forge in search of the

As

we passed to the rear of the house we met Marc Brier, dressed in

the traditional uniform of the Continental soldier. He explained

that "Von Steuben even shocked some of his fellow officers

when he hand picked 100 men from the field to personally train as

a unit." This unit quickly became the model by which other

training was measured. Day and night, von Steuben's commanding

voice could be heard in camp, directing, correcting and

re-directing. As regiments and then brigades began to pull

together in a single fighting force, pride and enthusiasm

re-emerged among the ranks and spirit of the army was rekindled.

As spring arrived new supplies and more men poured into the

valley and there was now a new alliance with France to bolster

their flagging spirits. On June 19, 1778, Washington marched out

of Valley Forge in search of the  British. He found Lt. Gen. Sir

Henry Clenton's British forces at Monmonth in New Jersey. The

report of some local rebel-rousers approaching brought smiles to

the British officers faces, but these

smiles quickly faded as they saw the snappy formations of

regiments quickly moving into formation. As the battle concluded,

only the American officers were smiling. The British had lost the

day, as they would eventually lose the war. The turning point in

this most significant part of American History was the lessons

learned while suffering the winter at Valley Forge.

British. He found Lt. Gen. Sir

Henry Clenton's British forces at Monmonth in New Jersey. The

report of some local rebel-rousers approaching brought smiles to

the British officers faces, but these

smiles quickly faded as they saw the snappy formations of

regiments quickly moving into formation. As the battle concluded,

only the American officers were smiling. The British had lost the

day, as they would eventually lose the war. The turning point in

this most significant part of American History was the lessons

learned while suffering the winter at Valley Forge.

* * * THE END * * *