Hopewell Furnace

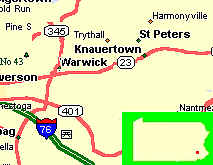

Rt 345.

Warwick, Pa.

August 3, 1999

As we drove from our campground Sun Valley to

Valley Forge on Rt. 23, we passed a sign showing "Hopewell

Furnace National Historic Site. Since we were heading for Valley

Forge we didn't want to take the time to check it out then, but

did on our way back. Unfortunately the park was getting ready to

close for that day and it looked interesting enough for a trip

back. Next day (Aug 3) we started out for the trip to Hopewell

Furnace. The trip from Rt. 23 to Hopewell Furnace on Rt 345 was

lovely. It was a two-lane road, lined with trees on each side.

The only drawback is that the drive is through a National Park

area and there are restrictions as to width and length of

vehicles that can travel on it.

we drove from our campground Sun Valley to

Valley Forge on Rt. 23, we passed a sign showing "Hopewell

Furnace National Historic Site. Since we were heading for Valley

Forge we didn't want to take the time to check it out then, but

did on our way back. Unfortunately the park was getting ready to

close for that day and it looked interesting enough for a trip

back. Next day (Aug 3) we started out for the trip to Hopewell

Furnace. The trip from Rt. 23 to Hopewell Furnace on Rt 345 was

lovely. It was a two-lane road, lined with trees on each side.

The only drawback is that the drive is through a National Park

area and there are restrictions as to width and length of

vehicles that can travel on it.

Upon approaching the Hopewell Furnace buildings, all you see is a

white building housing the Rangers' Office and

a small museum. However, if you look down over the hill you will

see an entire village. Before we went down to visit the village

we took time to find out something about Hopewell Furnace and its beginnings from Ranger Christine M. Almerico, Education

Coordinator.

white building housing the Rangers' Office and

a small museum. However, if you look down over the hill you will

see an entire village. Before we went down to visit the village

we took time to find out something about Hopewell Furnace and its beginnings from Ranger Christine M. Almerico, Education

Coordinator.

Hopewell furnace was originally built by Mark Bird in 1771. At

the time England was extremely concerned about the rapid

expansion of the industry in the colonies and the increasing

skill with which American ironmasters turned out cast and wrought

iron products. Due to this, England attempted to limit American

iron makers to just producing pig iron (rough cast bars) which

would be shipped to England and then processed into profitable

goods, which  would then be sold back to America. In spite

of these limitations, by the Revolution, American furnaces,

forges, and mills were turning out one-seventh of the world's

iron goods. Hopewell furnace was very successful due to

Pennsylvania's combination of abundant raw materials. By the time

Hopewell Furnace was built in Schuylkill Valley, Pennsylvania was

on its way to becoming the most important iron-producing colony.

Bird immediately began casting stove plates despite the British

ban, and when the war began he was a steady supplier of cannon

and shot to the Continental Army and Navy. As the war drew to an

end, however, Bird's financial troubles began to mount. Due to

these problems Bird ended up auctioning off what was then called

Hopewell Plantation at a sheriff's sale. Bird fled his remaining

creditors by moving to North Carolina. After this, Hopewell

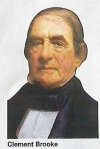

changed hands several times until Clement Brooke (a son of one of

would then be sold back to America. In spite

of these limitations, by the Revolution, American furnaces,

forges, and mills were turning out one-seventh of the world's

iron goods. Hopewell furnace was very successful due to

Pennsylvania's combination of abundant raw materials. By the time

Hopewell Furnace was built in Schuylkill Valley, Pennsylvania was

on its way to becoming the most important iron-producing colony.

Bird immediately began casting stove plates despite the British

ban, and when the war began he was a steady supplier of cannon

and shot to the Continental Army and Navy. As the war drew to an

end, however, Bird's financial troubles began to mount. Due to

these problems Bird ended up auctioning off what was then called

Hopewell Plantation at a sheriff's sale. Bird fled his remaining

creditors by moving to North Carolina. After this, Hopewell

changed hands several times until Clement Brooke (a son of one of

the owners) brought the operation to the peak

of its prosperity from 1816 to 1831. He presided over Hopewell

during its best years, when the furnace supplied a wide variety

of iron products to cities along the east coast. During this time

Hopewell used charcoal to fuel the huge furnace. In order to do

this an extremely large amount of timber was required. After

Brooke retired in 1848, Hopewell's owners found it increasingly

difficult to compete. They made efforts to keep up by building an

anthracite (coal) hot-blast furnace and installing a backup steam

engine, for the blast machinery. The new furnace was a failure,

and in any case their efforts only delayed the inevitable. Iron

plantations like Hopewell, were overtaken by the shift from the

age of iron and water power to the age of steel and steam, and

so, were unable to follow the industry into the 20th century. In

the summer of 1883, Hopewell Furnace made its final blast.

the owners) brought the operation to the peak

of its prosperity from 1816 to 1831. He presided over Hopewell

during its best years, when the furnace supplied a wide variety

of iron products to cities along the east coast. During this time

Hopewell used charcoal to fuel the huge furnace. In order to do

this an extremely large amount of timber was required. After

Brooke retired in 1848, Hopewell's owners found it increasingly

difficult to compete. They made efforts to keep up by building an

anthracite (coal) hot-blast furnace and installing a backup steam

engine, for the blast machinery. The new furnace was a failure,

and in any case their efforts only delayed the inevitable. Iron

plantations like Hopewell, were overtaken by the shift from the

age of iron and water power to the age of steel and steam, and

so, were unable to follow the industry into the 20th century. In

the summer of 1883, Hopewell Furnace made its final blast.