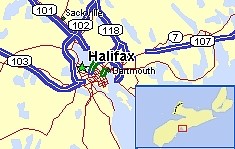

we

were staying near Halifax we decided to drive into town and see

what was available to be toured. One of the things that we found

was the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. From a modest beginning

in 1948 the Museum's collection has grown to be one of the

largest in the country, currently numbering in excess of 24,000

artifacts. They suggest that if you are limited for time,

consider visiting just two or three galleries. With two hours or

more, you'll have time to visit all of the galleries and

exhibits.

we

were staying near Halifax we decided to drive into town and see

what was available to be toured. One of the things that we found

was the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. From a modest beginning

in 1948 the Museum's collection has grown to be one of the

largest in the country, currently numbering in excess of 24,000

artifacts. They suggest that if you are limited for time,

consider visiting just two or three galleries. With two hours or

more, you'll have time to visit all of the galleries and

exhibits. There were so many exhibits that they were both inside and outside. On the outside they had the Museum's largest artifact the CSS Acadia. This ship was one of the first hydrographic research vessels to chart Canada's Artic and East coast waters. She is berthed at the Museum's wharf and is open May through October. Going inside we went to the small craft gallery. This displays many of over 50 small craft in the Museum's collection, which is one of the most extensive in Canada. Another exhibit was the Sable

Island exhibit, here you can visit Sable

Island and the Lifesaving Exhibit and learn about the

"graveyard of the Atlantic."

Island exhibit, here you can visit Sable

Island and the Lifesaving Exhibit and learn about the

"graveyard of the Atlantic." In addition they had exhibits on a Ship Chandlery. This would have been a store where sailors could go to buy their provisions. Then there was the days of sail gallery. They included stories of Nova Scotia's magnificent sailing vessels, from the barque Calburga to the coastal schooner Rayo. Included in and among much of this were treasures taken from over 10,000 shipwrecks which occurred in Nova Scotia's waters. Coming up to more modern times they include the modern cargo ships and elegant passenger liners that marked the passage to the age of steam. Because they have so many items for display it was not possible, at this time, to include them all in an exhibit. As a result, they have what they term a visible storage area. Here they display artifacts along with an explanation of what it is, where it was found, and what it was used for. Some of the items included here were astrolabes, binnacles, log-spinners and many, many more.

Two exhibits particularly stood out in my mind. They were the Titanic exhibit (1912) and the exhibit about the Halifax explosion which occurred in 1917. Although both were extreme disasters, they both exhibited the strength and resilience of the Canadian people.

The Titanic exhibit particularly interested me as it showed a great deal of information about the Titanic. I'm not sure that I realized that Halifax was one of the places that sent out ships (large cable-laying vessels) to assist in locating survivors of the wreck. Unfortunately, by the time the ships were able to be sent out from Halifax the majority of what they found were corpses. The crew took on the grisly task of loading the bodies onto the ship and bringing them back to Halifax to be identified by their city medical examiner, Barnstead. Barnstead's system proved

invaluable. It was used by his son to handle and identify the

2000 deaths in the Halifax Explosion in 1917. Even later, in

1992, Barnstead's meticulous records allowed researchers from

Titanic International to put names on six previously unidentified

Titanic graves.

invaluable. It was used by his son to handle and identify the

2000 deaths in the Halifax Explosion in 1917. Even later, in

1992, Barnstead's meticulous records allowed researchers from

Titanic International to put names on six previously unidentified

Titanic graves.When the Titanic departed Southampton, on April 10, 1912, her registered size and tonnage made her, for a short time, the largest ship in the world - in fact the largest moving object yet created. Titanic was an outstanding example of the art of riveted steel shipbuilding. Her steel plates were fastened by three million thick, steel pins called rivets. Riveting reigned supreme in shipbuilding for over a century, relegating wooden shipyards to oblivion and lasting until welding became common in World War II. Most people on the Titanic were doomed because she carried lifeboats for less than half those aboard, due to cost-cutting by White Star and outdated safety regulations. Most First Class passengers survived. In Third Class, however, many found themselves barred from the boat deck and were left to fend for themselves. George Wright a Halifax millionaire, had made his name publishing worldwide business directories. He was a noted yachtsman, an eligible bachelor and known for his support of moral causes such as housing for the poor. A heavy sleeper, Wright was not seen on the boat

deck and may have slept through the entire

catastrophe. His body was never found.

deck and may have slept through the entire

catastrophe. His body was never found.Separated from his wife, Navratil kidnapped their two children and fled aboard Titanic under an assumed name. He managed to get Edmond and Michel into the very last lifeboat. The boys were eventually reunited with their mother. Their father, however, was buried under his false name, Louis Hoffman, in the Baron de Hirsch Jewish Cemetery and not identified for several years. Halifax became the scene of the world's lasting legacy from theTitanic, the final resting place of her victims. Three Halifax cemeteries, Fairview Lawn (non-denominational), Baron de Hirsch (Jewish) and Mount Olivet (Cathollic) house 150 bodies. The graves range from the Presidential Secretary of the White Star Line to Titanic's violinist. About a third of the graves bear no names. One of the first victims to be buried was a small, unidentified boy. Mackay-Bennett's crew carried his body to the grave and paid for his tombstone. One exhibit showed what the sailors call wreckwood. Crews of the Halifax cable ships that recovered Titanic bodies followed an old tradition of keeping fragments of notable shipwrecks. Anonymous pieces of wood from Titanic were also carved into keepsakes, such as picture frames, cribbage boards and paperweights. They were not sold as souvenirs but kept by the families of crewmen, often treasured for generations as relics of their connection to the sinking.

The

second

disaster which hit the people of Halifax on a much more personal

level was the explosion which occurred in 1917. This exhibit

recounts the devastating effects of the largest man-made

explosion before the atomic age. The story about how the

explosion came about and what came afterward is one of chance and

unbelievable bravery. The explosion was caused by two ships,

going to war, that collided in the Halifax harbor which killed

several thousand people and did much damage to buildings along

the waterfront. The French ship Mont Blanc had been loaded in New

York by longshoremen wearing cloth covers on their boots. Her

holds contained high explosives; barrels of benzol, a type of

gasoline, were stowed on her open decks. Too slow for the convoy

that was about to leave New York, she was ordered to Halifax

where a slower one was being formed. She arrived on December 5,

too late to pass through the anti-submarine nets.

second

disaster which hit the people of Halifax on a much more personal

level was the explosion which occurred in 1917. This exhibit

recounts the devastating effects of the largest man-made

explosion before the atomic age. The story about how the

explosion came about and what came afterward is one of chance and

unbelievable bravery. The explosion was caused by two ships,

going to war, that collided in the Halifax harbor which killed

several thousand people and did much damage to buildings along

the waterfront. The French ship Mont Blanc had been loaded in New

York by longshoremen wearing cloth covers on their boots. Her

holds contained high explosives; barrels of benzol, a type of

gasoline, were stowed on her open decks. Too slow for the convoy

that was about to leave New York, she was ordered to Halifax

where a slower one was being formed. She arrived on December 5,

too late to pass through the anti-submarine nets. Thursday, December 6, dawned clear. The French munitions ship, Mont Blanc, had spent the night anchored off McNab's Island. It proceeded up the harbour to join the convoy gathering in Bedford Basin. The Norwegian ship, Imo, left the Basin, heading out to sea. At 8:45 a.m. Imo's bow struck Mont Blaanc, tore her hull and created a shower of sparks. Fire broke out, quickly spreading through the ship. Taking to the lifeboats, Mont Blanc's crew rowed frantically for the Dartmouth shore. The huge column of black smoke, with spurts of flame bursting through, attracted crowds of spectators. Slowly, the burning ship drifted towards Halifax and came to rest at Pier 6. Seconds before 9:05 a.m. Mont Blanc blew up.

Captain Horatio Brannen was in command of the tug Stella Maris. After the collision between Imo and Mont Blanc, he gave orders to anchor the scows his ship had towed and approach the burning vessel. His firehoses proved useless against such a fire. When Mont Blanc exploded, Captain Brannen and his crew were trying to fix a tow to drag the ship away from Pier 6. Stella Maris was badly damaged. Captain Brannen and eighteen of her twenty-four crew were killed. Captain Brannen had had a portrait taken which was intended as a Christmas gift for Mrs. Brannen. She was told of it and went to the photographer's studio, where the owner presented an extra framed copy to the captain's small daughter. Again, Medical Examiner Barnstead's system proved invaluable. It was used by his son to handle and identify the 2000 deaths in the Explosion.

If you get in the Halifax area I would highly recommend a visit to the Maritime Museum. By all means be sure and wear your walking shoes and allow yourself plenty of time. It would be a shame to have to rush through such a wonderful place.

To visit their website go to: http://maritime.museum.gov.ns.ca.