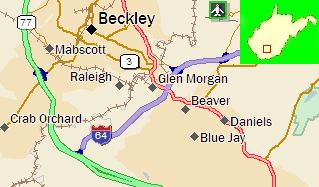

Beckley Exhibition Coal

Mine

513 Ewart Ave

Beckley, WV 25802

May 10th, 2008

Have you ever been down in a coal mine? A real coal mine. Well I had not,

so when a opportunity arrived to visit such a dark and damp place I jumped at

the chance. We had been traveling from Virginia to a summer haunt in Ohio

and had stopped in Beckley for a night which became a week. The Beckley Exhibition

campground is just a small part of the conglomerate made up of the mine, the Mountain

Homestead Museum, and the Youth Education center. Having made our

introductions at the office, we acquired our tickets to ride and headed down to

the old electric car barn where we

you ever been down in a coal mine? A real coal mine. Well I had not,

so when a opportunity arrived to visit such a dark and damp place I jumped at

the chance. We had been traveling from Virginia to a summer haunt in Ohio

and had stopped in Beckley for a night which became a week. The Beckley Exhibition

campground is just a small part of the conglomerate made up of the mine, the Mountain

Homestead Museum, and the Youth Education center. Having made our

introductions at the office, we acquired our tickets to ride and headed down to

the old electric car barn where we  would

start our tour. Here we met Cliff Chandler, a 70 something year old miner

who had spent some 40 years in the mines and would be our tour guide and train

operator. Cliff explained that most of the things he was going to talk

about were down in the mine so we talked about general items. I learned

that the mine once produced a good grade of coal but the vein finally became too

small to be worthwhile and in 1910 it closed. It lay dormant until

1962 when it opened up as a museum. The little train cars we would be

riding in would be pulled by an electric engine he called a coal puller, or

gathering motor built sometime around 1930. It was slow but very powerful.

He estimated that the tracks we would be using today were laid out in about a

200 foot long circle

would

start our tour. Here we met Cliff Chandler, a 70 something year old miner

who had spent some 40 years in the mines and would be our tour guide and train

operator. Cliff explained that most of the things he was going to talk

about were down in the mine so we talked about general items. I learned

that the mine once produced a good grade of coal but the vein finally became too

small to be worthwhile and in 1910 it closed. It lay dormant until

1962 when it opened up as a museum. The little train cars we would be

riding in would be pulled by an electric engine he called a coal puller, or

gathering motor built sometime around 1930. It was slow but very powerful.

He estimated that the tracks we would be using today were laid out in about a

200 foot long circle  which

looped back into itself near the entrances. After a short wait for the

other passengers, we boarded the cars and were soon creeping down the

mine. We had not left the light of the entrance when the temperature

dropped and the humidity jumped up. Cold and damp is a reality of the

mine. Water dripped from the ceiling in most places. On we

crept

into the darkness until the only light was from a single small light bulb

suspended from a lone power line strung across the ceiling near the walls.

The passage was short and narrow, narrow to the point of almost

hitting the walls with the carts. When we did stop and were allowed to get

out and look about, there usually

was not enough headroom to stand up. Our first stop was at a widened part of

the mine where there were several items that Cliff talked about. In his

soft West Virginia accent, he explained that the end of the 1800s was not a good time to

which

looped back into itself near the entrances. After a short wait for the

other passengers, we boarded the cars and were soon creeping down the

mine. We had not left the light of the entrance when the temperature

dropped and the humidity jumped up. Cold and damp is a reality of the

mine. Water dripped from the ceiling in most places. On we

crept

into the darkness until the only light was from a single small light bulb

suspended from a lone power line strung across the ceiling near the walls.

The passage was short and narrow, narrow to the point of almost

hitting the walls with the carts. When we did stop and were allowed to get

out and look about, there usually

was not enough headroom to stand up. Our first stop was at a widened part of

the mine where there were several items that Cliff talked about. In his

soft West Virginia accent, he explained that the end of the 1800s was not a good time to

work in a mine.

Because the only tools used were picks, shovels and dynamite, mines were never

expanded beyond the coal vein. The vein in this mine was only about 3 feet

high which meant that the miners spent their entire workday on their

knees. The dynamite would break up the vein, then the miners would pick it

free and shovel it into either one or two ton coal cars. Working steadily

with only a few breaks, a miner could fill as many as 10 one ton cars. For

this he would be paid about 20 cents per car. Giving

him, hopefully, $2.00 a day for his effort. But there were expenses to this

job. The miner had to pay for rent of the company owned cottage that he

lived in. The coal he used in his small heating stove was not free, nor

was his food. In the mine, he was responsible for most of the expense of

getting the coal out, including the dynamite, as well as the timbers he used to shore up the ceiling

around him. At the end of the day, there just wasn't that much left, but

of course the mine owners had the answer for that. Highly elevated priced

goods at the company store. A miner could borrow mine scrip, often in coin

form which could be spent at the company operated

work in a mine.

Because the only tools used were picks, shovels and dynamite, mines were never

expanded beyond the coal vein. The vein in this mine was only about 3 feet

high which meant that the miners spent their entire workday on their

knees. The dynamite would break up the vein, then the miners would pick it

free and shovel it into either one or two ton coal cars. Working steadily

with only a few breaks, a miner could fill as many as 10 one ton cars. For

this he would be paid about 20 cents per car. Giving

him, hopefully, $2.00 a day for his effort. But there were expenses to this

job. The miner had to pay for rent of the company owned cottage that he

lived in. The coal he used in his small heating stove was not free, nor

was his food. In the mine, he was responsible for most of the expense of

getting the coal out, including the dynamite, as well as the timbers he used to shore up the ceiling

around him. At the end of the day, there just wasn't that much left, but

of course the mine owners had the answer for that. Highly elevated priced

goods at the company store. A miner could borrow mine scrip, often in coin

form which could be spent at the company operated store only and then would be

taken out of his pay at the end of the two week pay period. Some miners

with families often spent more in script then they made in the mines, giving

rise to the words of a famous Tennessee Ernie Ford song "I owe my soul to

the company store". The single weak light bulb which created great

shadows with its soft glow, as we listen, didn't exist when this mine was in its heyday.

Instead, miners used an even weaker light made by a single candle-like flame

from a carbide lantern on his

store only and then would be

taken out of his pay at the end of the two week pay period. Some miners

with families often spent more in script then they made in the mines, giving

rise to the words of a famous Tennessee Ernie Ford song "I owe my soul to

the company store". The single weak light bulb which created great

shadows with its soft glow, as we listen, didn't exist when this mine was in its heyday.

Instead, miners used an even weaker light made by a single candle-like flame

from a carbide lantern on his  helmet. Water was added to a carbide block

which created the gas needed for the flame. A small striker wheel just

like an old cigarette lighter mounted below the flame nozzle was used to ignite

the flame. One of the major problems with this was that coal mines are notorious

for creating methane gas pockets. Explosions were a far greater danger back

then, then they are today. To remedy this, the mines created one of the most

unpopular jobs there was. Some poor miner got to take his carbide lantern

and climb up in each crack and crevice to burn off the pockets of gas before

they got so big they would explode, he hoped. Many a miner's last day on

the job was finding a pocket that had grown larger then the small bright

flashover he had hoped to cause. Still, pockets of the deadly gas could

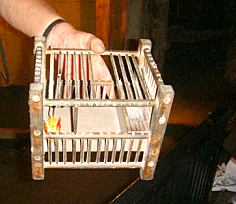

slip by undetected. For those who could afford it, a miner might have a small

cage containing a canary. As long as the bird sang, the miner would

work. When the bird quit chirping, it was time to leave, and most likely

buy another bird.

helmet. Water was added to a carbide block

which created the gas needed for the flame. A small striker wheel just

like an old cigarette lighter mounted below the flame nozzle was used to ignite

the flame. One of the major problems with this was that coal mines are notorious

for creating methane gas pockets. Explosions were a far greater danger back

then, then they are today. To remedy this, the mines created one of the most

unpopular jobs there was. Some poor miner got to take his carbide lantern

and climb up in each crack and crevice to burn off the pockets of gas before

they got so big they would explode, he hoped. Many a miner's last day on

the job was finding a pocket that had grown larger then the small bright

flashover he had hoped to cause. Still, pockets of the deadly gas could

slip by undetected. For those who could afford it, a miner might have a small

cage containing a canary. As long as the bird sang, the miner would

work. When the bird quit chirping, it was time to leave, and most likely

buy another bird.

On down we traveled in our slow moving train which shook

and wobbled at every turn, until we arrived at other destinations with other

stories. At one particular stop we learned

about the lunch bucket. In the days of this mine there was no cafeteria

topside that the miners could go to during their hour lunch break. There were no

lunch breaks. Miners ate whatever they brought with them on the job, on

their own time, and time was money. The lunch pail was pretty universal, aluminum,

round and with a second bucket taking up half of the inside. The pail was filled half full of water

and then the top pail was placed over the water. The second pail contained the

food. With any luck the miner would find a "widow maker" nearby to sit

on while he ate, like the one the pail is sitting on

in the picture. A widow maker was created eons ago when trees stumps

protruding down to where the mine would be, were petrified, then millions of

years later, cut off when the mine was dug, leaving the stump's upper

portion embedded in the ceiling. Although the stump itself was now a hard stone

often weighing hundreds of pounds, the bark which had been around it, had

turned to coal rather then stone. As work continued in the mine, the coal around

the stump would loosen and the stone stump would come crashing down to the mine

floor, with often fatal results if a miner was walking by at that precise

moment. In any case, another miner's dining seat was created. The

miners had only the water they brought, so if a miner ran out, well, all miner's

pails looked alike. To prevent water loss from such "mistakes", miners would

often leave a set of false teeth in the water to prevent others from taking more

than they had brought for themselves. Cliff was a treasure trove of trivia-like facts about the life in the mines. One of the more common creatures

to be found deep in a mine were rats. I would have thought that with such

a sparse environment that such animals could not have survived long. They

owed their survival to the miners. No meal was complete until a little

food had been left for the rats. What might sound like a far-fetched tale

or at best some superstition, was actually rooted in decades of experience and

observation. As Cliff explained, years of mining had taught the miners

that rats have a sixth sense about survival. The lesson taught by these

small creatures was that "If you see the rats running by you in number, run

the same way! You are probably minutes if not seconds from

disaster." Many an early century miner owed his life to this

knowledge.

which had been around it, had

turned to coal rather then stone. As work continued in the mine, the coal around

the stump would loosen and the stone stump would come crashing down to the mine

floor, with often fatal results if a miner was walking by at that precise

moment. In any case, another miner's dining seat was created. The

miners had only the water they brought, so if a miner ran out, well, all miner's

pails looked alike. To prevent water loss from such "mistakes", miners would

often leave a set of false teeth in the water to prevent others from taking more

than they had brought for themselves. Cliff was a treasure trove of trivia-like facts about the life in the mines. One of the more common creatures

to be found deep in a mine were rats. I would have thought that with such

a sparse environment that such animals could not have survived long. They

owed their survival to the miners. No meal was complete until a little

food had been left for the rats. What might sound like a far-fetched tale

or at best some superstition, was actually rooted in decades of experience and

observation. As Cliff explained, years of mining had taught the miners

that rats have a sixth sense about survival. The lesson taught by these

small creatures was that "If you see the rats running by you in number, run

the same way! You are probably minutes if not seconds from

disaster." Many an early century miner owed his life to this

knowledge.

Although the props are pretty much the same on every trip to the mine,

each miner guide has his own unique set of stories, trivia, and jokes.

This would make the trip worthwhile even if you have read this article.

***THE END ***