Andersonville

National

Historic Site

Andersonville

GA

November 30, 2001

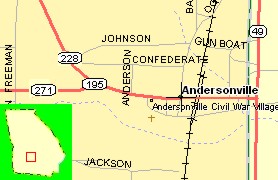

This week found us in

central Georgia reviewing yet another civil war memorial. Our

friends, the Tarkins had written in their gypsy journal about a

small city campground at Andersonville, Ga. They had made the

place sound so interesting we decided to try it. We were not to

be disappointed. South central Georgia is the home of peaches,

cotton and that wonderful delicacy, pecans. In addition to all

the other benefits, each morning would find me off walking the

lanes surrounding the small quaint village, armed with my home

made Pecan picker, a walking stick with a piece of paper tape

attached to one end. The town was created in 1853 as a train stop

community. It is not much bigger today. A solitary monolith in

the middle of the street is the only reminder of a man who would

die in infamy on the gallows for act which he may or may not have

had any control over. Peggy Sheppard, the author of

"Andersonville Georgia U.S.A.", a documentary

found us in

central Georgia reviewing yet another civil war memorial. Our

friends, the Tarkins had written in their gypsy journal about a

small city campground at Andersonville, Ga. They had made the

place sound so interesting we decided to try it. We were not to

be disappointed. South central Georgia is the home of peaches,

cotton and that wonderful delicacy, pecans. In addition to all

the other benefits, each morning would find me off walking the

lanes surrounding the small quaint village, armed with my home

made Pecan picker, a walking stick with a piece of paper tape

attached to one end. The town was created in 1853 as a train stop

community. It is not much bigger today. A solitary monolith in

the middle of the street is the only reminder of a man who would

die in infamy on the gallows for act which he may or may not have

had any control over. Peggy Sheppard, the author of

"Andersonville Georgia U.S.A.", a documentary on the history of the prison and the town, talked with us outside

the visitor's center. We learned much of what had happened here,

from her as she walked with us through the Pioneer Village, which

is maintained by the town. In 1864, the town, and the landscape

changed forever. The Civil War was raging and prisoner exchanged

between the North and South had broken down. Both sides found

themselves with literally thousands of prisoners and no

facilities to handle them. About a mile away, two hills separated

by a small stream became the most notorious prison in American

History. Sixteen and a half acres were closed in by a 15 foot

wall of hand hewn pine logs. Every 88 feet or so, a tower was

built from which a sharpshooter stood guard. About 20 feet inside

the fence was a death line, marked by a single pole running

horizontally about 3 feet off the

on the history of the prison and the town, talked with us outside

the visitor's center. We learned much of what had happened here,

from her as she walked with us through the Pioneer Village, which

is maintained by the town. In 1864, the town, and the landscape

changed forever. The Civil War was raging and prisoner exchanged

between the North and South had broken down. Both sides found

themselves with literally thousands of prisoners and no

facilities to handle them. About a mile away, two hills separated

by a small stream became the most notorious prison in American

History. Sixteen and a half acres were closed in by a 15 foot

wall of hand hewn pine logs. Every 88 feet or so, a tower was

built from which a sharpshooter stood guard. About 20 feet inside

the fence was a death line, marked by a single pole running

horizontally about 3 feet off the ground. The land between the death line and the

fence was a free fire killing zone. Many a Union prisoner would

end his agony by simply walking within the bounds and inviting a

shot. The prison was destined to last for only 14 months.

Originally built to house 6000 prisoners, it would swell to over

32,000 by 1865. The small creek, called Stockade Creek became the

sole source of water until late in the year when a well broke

through after a storm. One end of the creek was for drinking and

the other end was for human waste. Baths were taken in the

middle. The creek was blocked at its exit to prevent

contamination further downstream. There simply were no housing

facilities inside the stockade.

ground. The land between the death line and the

fence was a free fire killing zone. Many a Union prisoner would

end his agony by simply walking within the bounds and inviting a

shot. The prison was destined to last for only 14 months.

Originally built to house 6000 prisoners, it would swell to over

32,000 by 1865. The small creek, called Stockade Creek became the

sole source of water until late in the year when a well broke

through after a storm. One end of the creek was for drinking and

the other end was for human waste. Baths were taken in the

middle. The creek was blocked at its exit to prevent

contamination further downstream. There simply were no housing

facilities inside the stockade.  The prisoners were marched into the stockade and

turned loose to fend for themselves. They had a tendency to group

together according to States. All the boys from Ohio being in one

place and the ones from Indiana in another. With no shelter it

was every man for himself. Gathering whatever material they could

find on the ground or acquire on many of the out-of-stockade

details, small lean-to structures were built.As we walked through

the site with our guide, Jennifer Gainous, she explained that

these shelters were known as Shebangs, and usually held from 4 to

6 people. As

The prisoners were marched into the stockade and

turned loose to fend for themselves. They had a tendency to group

together according to States. All the boys from Ohio being in one

place and the ones from Indiana in another. With no shelter it

was every man for himself. Gathering whatever material they could

find on the ground or acquire on many of the out-of-stockade

details, small lean-to structures were built.As we walked through

the site with our guide, Jennifer Gainous, she explained that

these shelters were known as Shebangs, and usually held from 4 to

6 people. As  conditions worsened, the death rate from disease

rapidly increased until there were over 100 people a day dying

from heat, exposure and illness. It is believed that an

expression was born of the devastation. If you woke up in your

shelter to find that all the others in there with you had died

during the night, you were said to have "The whole

shebang" to yourself, until others found out and moved in.

The man responsible for the prison was a Confederate Army Captain

named Henry A Wirz. Captain Wirz was a Swiss born American who

joined the Confederacy as a Sergeant. He was hit in the right

wrist with a mini-ball at the Battle of Seven Pines. With a wound

that would have sent most soldiers home, he continued on, being

promoted to Captain and serving in several ranking administrative

positions before being assigned to prison duty which resulted in

his duties at Andersonville.

conditions worsened, the death rate from disease

rapidly increased until there were over 100 people a day dying

from heat, exposure and illness. It is believed that an

expression was born of the devastation. If you woke up in your

shelter to find that all the others in there with you had died

during the night, you were said to have "The whole

shebang" to yourself, until others found out and moved in.

The man responsible for the prison was a Confederate Army Captain

named Henry A Wirz. Captain Wirz was a Swiss born American who

joined the Confederacy as a Sergeant. He was hit in the right

wrist with a mini-ball at the Battle of Seven Pines. With a wound

that would have sent most soldiers home, he continued on, being

promoted to Captain and serving in several ranking administrative

positions before being assigned to prison duty which resulted in

his duties at Andersonville.